In the 1980s, an inventor named Stanley Meyer unveiled an invention that he said could revolutionize the car and energy industries, a car that was fueled by only water. According to Meyer, his invention could electrolyze water into individual atoms, then it would use the hydrogen to run the car’s engine with over 100% efficiency, a process that would break the laws of thermodynamics. However, nobody was ever able to see the inner workings of the car, nor has anyone ever replicated his work. Season 3, Episode 8 of The Conspiracy Show with Richard Syrett entertains the idea that the idea was functioning and that Stanley was murdered. When analyzed, the claims about the water engine being functional can be proved false using basic principles of chemistry and thermodynamics.

The total energy of an isolated system is constant; energy can be transformed from one form to another, but cannot be created or destroyed.

Ron Milione, an electrical engineer and inventor of 25 years, believes that Meyer’s design was functional. “Stanley Meyer, he absolutely [created a functional water-powered car]” (3:10) He is not qualified to support a claim like this. He is speaking outside of his area of expertise as he is actually an electrical engineer, not a chemist or atomic physicist. Another way he showed his bias was by talking about his distrust for large oil corporations. This suggests that he may have motivated reasoning towards believing an invention that oil companies may be threatened by, and believing that they suppressed Meyer because of it. The fact that he doesn’t trust oil companies means that he’ll speculate further in a biased way and it will make his theories more exaggerated because of his personal opinions, not any evidence. He’s jumping to conclusions, and cherry-picking the ‘evidence’ that support his theory that oil companies are corrupt.

Olev Trass, Professor Emeritus of Chemical Engineering at the University of Toronto, calls Meyer’s claims “outlandish” (5:59) and states that “It is impossible according to first order thermodynamics.” (6:42) Trass explains how it disagrees with the first law of thermodynamics, “the amount of energy going into system [sic] cannot be smaller than the amount of energy going out” (6:14) Furthermore, because the electrolysis of water is an endothermic process, meaning it needs energy to happen, it would take more energy to electrolyze the water than what would be produced from burning the hydrogen.

Attempts to capitalize on Meyer’s technology have failed consistently.

Ozzie Freedom, founder of WATER4GAS (now HydroXSystems), explains how he’s attempted to use Stanley’s work to improve the fuel efficiency in regular, gasoline-burning cars; “When you put 12 volts into the water it starts doing something called electrolysis. [It] splits the water into hydrogen and oxygen, now you take that hydrogen and you throw it into the engine […], and it makes the fuel there burn better than what the car engineers have done. You’re making it better but by this little addition the hydrogen makes the fuel burn better.” (16:07) Freedom’s technology does not function how he explains, and for the same reason that Meyer’s doesn’t. It takes more energy to separate water molecules via electrolysis than what is produced by combusting the hydrogen.

Ozzie later claims a quantitive gain, and explains another benefit of using some hydrogen to fuel your car: “I get 24 miles a gallon now and I can use a cheaper gas because this is like adding 130 octane.” (17:02) Just like his other claims, there are multiple problems with these. When installed, it is connected to the fuel lines and the alternator. (see figure 1) The main problem with this concept is that they produce too little hydrogen to be effective. When comparing how much air an engine requires to run, the amount of hydrogen used instead of air is almost negligible. In fact, because it takes electricity to electrolyze the water, the engine has to work harder to produce the energy needed from the alternator. This means that there would actually be a small decrease in vehicle efficiency. Another problem in his claim is when he states that it’s similar to running 130 octane fuel. The benefit to running higher octane fuel is that the combustion is not sudden. This prevents early detonation and increases the lifespan of the engine. Freedom did not mention anything about engine longevity or preventing early detonation. This can be considered an example of using jargon to sound educated, or to make his invention sound better than what it is.

Figure 1. A WATER4GAS system installed to a car engine. Freedom checks the cell voltage of the electrodes using a multimeter. “The Water Engine“

No, Big Oil was not out to get Meyer, and he wasn’t murdered.

Milione describes the circumstances surrounding Meyer’s death: “Stanley takes his sip and within not even a minute he basically starts to shake, stands up, tries to run out the exit of the restaurant, [then,] Stan goes ‘I don’t know what’s going on, but I think I was poisoned,’ and a couple of minutes later he’s dead, right there” (10:35) The story of Meyer’s death is often disputed. While it’s generally agreed upon and proven via an autopsy that his cause of death was a cerebral aneurysm, some cite ‘Big Oil,’ or large oil corporations such as Exxon-Mobil for the cause of his death.

Ozzie Freedom, founder of WATER4GAS, tells the story of an attempted buyout of Meyer’s work. “Some guys from belgium representing some energy enterprise, they wanted to buy his patents and his technology. As I gathered, he actually refused. I think it was a quarter billion or something and once he refused and he was announcing that he was going to do it himself, he was eliminated by poisoning or something like that.” (13:30) Not only is this an extraordinary claim, which, by the Sagan Standard requires much stronger evidence, especially more than just word of mouth. But, it conflates possibility with actuality. It’s implying that because he was just meeting with investors, and that they just had a disagreement, there’s no other possible explanation for how Meyer died. Milione attempts to make the story more credible by personalizing the situation when he says “Wouldn’t you want to stop somebody if they’re going to put [you] out of billions [of dollars] worth of business?” (15:07) Milione expects that most people would agree with that statement. The truth is that most people will never be in that situation. It’s highly unlikely for anyone to be tested in that way. Additionally, Milione is showing signs of bias. Firstly, by assuming that the cause of Meyer’s death was done by powerful people with malicious intentions, he’s showing attribution bias. Secondly, he’s showing agency bias by assuming that there was an intent behind a coincidental event such as Stanley’s death, that is, to supress his ideas and attempt to prevent his invention from being released to the public.

There’s inconclusive evidence of the machine actually functioning solely using water as fuel.

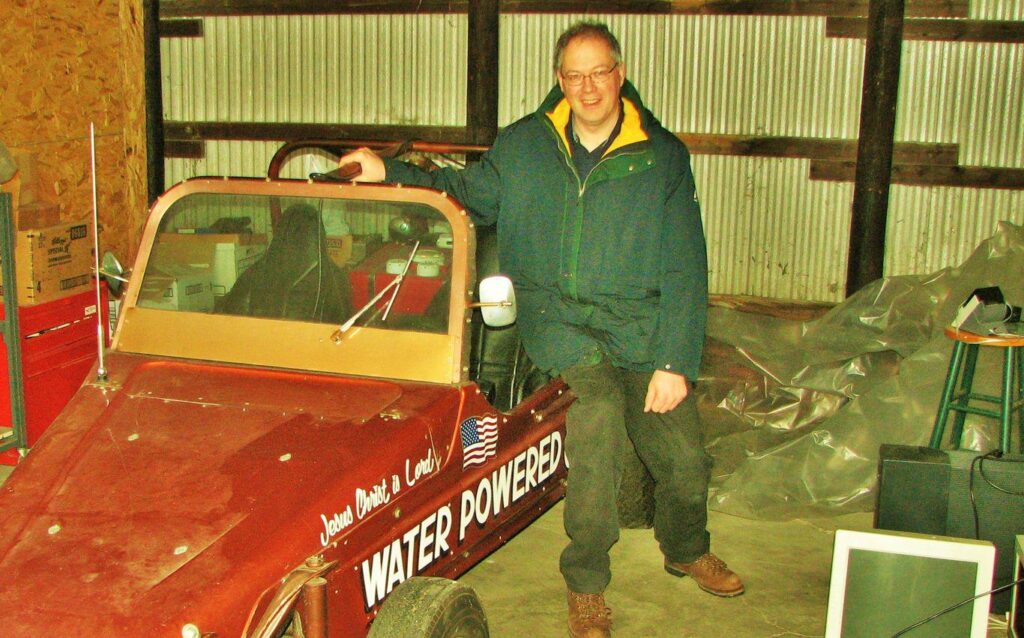

At 1:43 in the episode, Richard Syrett mentions that “no one has been able to duplicate meyer’s achievement since his death.” The lack of any detailed technical data or reproducible results from his experiments has made it hard for scientists to accept his invention as viable. Meyer wouldn’t even allow a prototype to be shown to, much less given to scientists or research organizations. He also neglected to show any more than the exterior of the car to anyone. (Refer to figure 2) Attempts by other researchers to duplicate Meyer’s results have consistently failed, which has raised serious doubts about the authenticity of his claims.

Bruce Simpson, writer of over 25 years for his New Zealand-based online news and commentary publication, Aardvark, argues that “[fraudulent inventors] come up with an idea that has a basis in good science (electrolysis) and then claim to have developed some major breakthrough that extends it into the realm of miracle. To try and make themselves credible, they steal little snippets of science from other areas (such as resonance) and patch it into what seems (in the eyes of those with a grade-school understanding of science), a credible explanation.” (Simpson) This shows how Meyer used imprecise vocabulary and jargon to make himself appear more credible. In addition to this, Meyer would ‘wear’ his PhD by mentioning it as evidence that he was a credible innovator. His PhD, unsurprisingly, was in an unrelated field, Natural Medicine. Furthermore, it is alleged that Meyer received his degree from a friend who was an administrator for a university.

figure 2. Stanley Meyer sitting on his alleged water powered car. “The Mysterious Death“

There are problems with Stanley’s patent.

There’s another problem in a statement made by Milione. He assumes that the invention works when he mentions that it’s patented: “[H]e absolutely did it and he actually created a patent on it.” (3:10) Patents do not need to be functioning to be approved. Bruce Simpson explains that “there is the misconception that gatting a patent for a device is some kind of proof that it works – which is ‘patently’ untrue. The patent office doesn’t test the designs it processes, it is simply a clerical operation where checks are made that the submitted documents meet certain criteria for completeness and correctness. There are a great many [sic] patents issued every year for devices that simply do not work.” (Simpson) This means that Milione cannot use a patent as proof of functionality. On top of that, Meyer’s patent and the included notes show and talk about how the design utilizes resonant frequencies to dissociate the water. These descriptions have been criticized for a lack of detailed methodology.

The details in the patents make it not possible to replicate the design using the patents alone. This led many people, such as Ozzie Freedom, to conclude that parts of the design were deliberately withheld in order to protect from copying. He states that “I think [that] what happened was that his patents could not be replicated because he left out some important parts. So, the patent was used to publish enough to protect his technology but not to give it out.” (12:02) This shows a strong confirmation bias. Freedom is already convinced that Meyer’s invention was functional, and when given clear evidence against that, he tries to find problems with the evidence.

Conclusion

Stanley Meyer and his water fuel cell is a story of ‘innovation,’ controversy, and fraud. Meyer’s invention, which broke the laws of chemistry and thermodynamics, never had its claims verified or its inner workings shown to anyone. The lack of anyone using his patents and technologies today cast a lot of doubt on whether what he was doing was legit. How much attention his invention garnered and how there have been commercial attempts with the same principle just go to show how much interest there is in clean energy sources. The conspiracy theories about his death just go to show how much people don’t trust the government or big companies. These theories, even though they’re not proven, show how much intrigue and hope is sometimes placed in revolutionary inventions and claims. They show how we need to hyperanalyze every revolutionary claim and think of it as guilty until proven innocent. For example, the products that try and use electrolysis to improve vehicle efficiency show how it can be challenging to apply those concepts to the real world. It shows how important regulations and consumer protections are, especially when there’s the potential for misleading or exploiting investors and the general public. In conclusion, Stanley Meyer’s story is a good lesson about the dangers of pioneering or investing in uncharted territories. It shows how we need a more informed public and emphasizes how important scientific verification is, which will drive innovation and let the public trust new inventions, concepts, the government, and large companies.

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment